Preventing child sexual abuse

Donald Findlater considers what it might take to eradicate child sexual abuse

Eradicating child sexual abuse will require huge efforts by many people, most of whom will not be professionals in the fields of social work, child protection, or law enforcement. Whilst not diminishing the crucial role such professionals can and do play, it is vital that we recognise the particular complexities of child sexual abuse and the necessity for designing and implementing tailored responses.

In this article I will describe what child sexual abuse prevention does or might look like. I use the journey I have made over the past 30 years – from providing sex offender treatment programmes in the Probation Service to directing the development of prevention services with the child protection charity, the Lucy Faithfull Foundation (LFF) – to challenge some thinking about sex offending and its inevitability, and hopefully to stimulate greater interest in the prevention of sexual harm to children.

Safeguarding: whose responsibility?

First, consider what it might take to prevent the sexual abuse of a 15-year-old female pupil by her 28-year-old male teacher on school premises? If we could roll back the clock, what circumstances might we alter to prevent the abuse from happening in the first place? How would we make things different for the 15year-old, for her friends, her parents, the abusive teacher, his colleagues and bosses. What about the physical layout of the school where the abuse will take place? In a similar way, consider how to prevent the re-abuse of a seven-year-old male child by a 16-year-old female who regularly babysits him. Or the two-year-old female child abused in a nursery setting by an adult female worker. The scenarios, and the impact on the different children, are many and varied. The prevention of all these examples of abuse requires a range of approaches involving diverse people, few of whom will be child protection professionals. Nonetheless, prevention must be made possible.

Over the past 30 years, we have come to understand a great deal about sexual abuse and sexual abusers –about the ‘who’, the ‘how’ and the ‘where’ of abuse. Sadly, I do not believe we are making the most effective use of what we know to prevent sexual abuse. Strategies to protect children typically address only part of the problem, with politicians and commentators seeming to believe that concentrating efforts on expensive criminal justice responses will reap vast rewards. This belief ignores the evidence that only a small minority of offenders are ever convicted; that those convicted are often not the most risky; and that desistance is actually the norm for this offender group. The predatory, determined, repeat offender is in the minority; yet policy and practice often assume otherwise. This criminal justice focus is an irrelevance for most child victims of sexual abuse within the family (the context of the greatest risk for children), with seven out of eight victims not reporting, and only a small minority of reported offences achieving a conviction (Children’s Commissioner 2015).

Theoretical perspectives

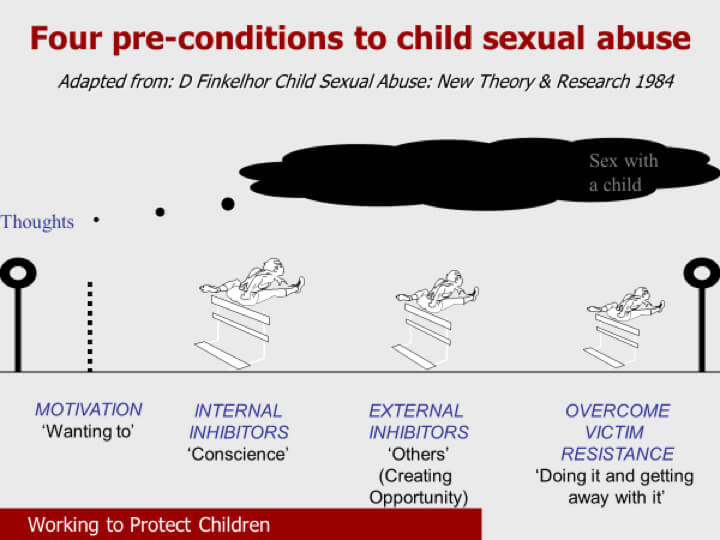

David Finkelhor’s “Four preconditions to child sexual abuse” describes a process that involves: the development of a motivation to abuse; the overcoming of conscience; the avoidance or manipulation of potential protectors (termed “external inhibitors”); and the grooming and abuse of the child victim.

Finkelhor’s four pre-conditions to child sexual abuse

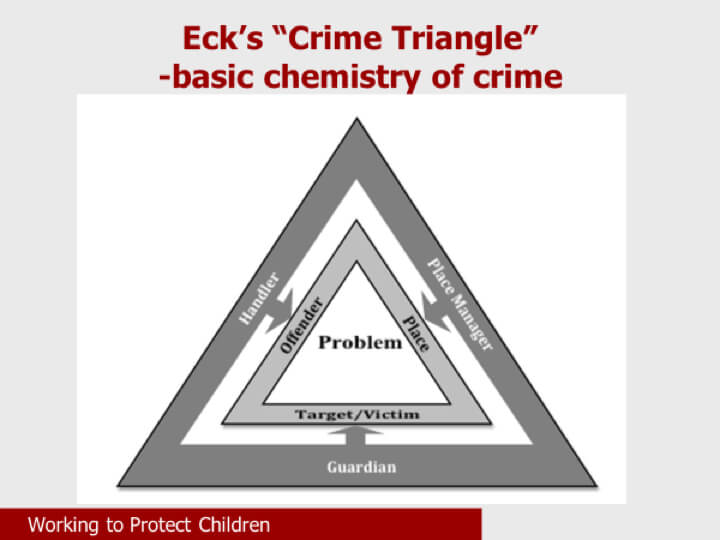

Five years earlier, criminologists Cohen and Felson proposed a ‘basic chemistry of a crime’. Many people have the potential to offend but do not. To convert their criminal potential into criminal actions, they need the opportunity to encounter a suitable target in the absence of a capable guardian. Eck further developed thinking about “situational prevention” and the preventative role of third parties by proposing three types of ‘crime controller’. ‘Guardian’ refers to persons with the responsibility and capacity to protect the potential victim – for example parents or teachers. ‘Handlers’ are those who can exert a positive influence on potential offenders – such as parents, friends and work colleagues. ‘Place managers’ are responsible for supervising and maintaining good conduct in specific physical locations where risk might manifest, eg schools and parks.

Eck proposed three types of guardian who could protect the potential victim of child sexual abuse

For the present purposes, I must also mention criminological thinking about developmental crime prevention. ‘Its aim is essentially to reduce criminal propensity by intervening early to forestall the negative effects of certain developmental circumstances and experiences’ (Smallbone & McKillop 2014). Problematic sexual outcomes have been linked to individual impulsivity, poor problem solving and family adversity, including domestic violence and parental substance misuse. For some boys, the experience of sexual abuse in childhood is coming to be recognised as a risk factor for sexual offending. Early interventions to ameliorate the impact of these adverse childhood experiences may reduce the development of motivation to abuse, including reducing any inter-personal difficulties the young person might face. These are at last becoming targets in some intervention programmes for convicted offenders. What might have been the outcome had we offered these interventions sooner?

The practice of prevention

My involvement in prevention started with sex offender treatment programmes within the Probation Service in the 1980s, followed by work in the more intensive Wolvercote Clinic residential assessment and treatment programme, which operated between 1995 and 2002. Broadly cognitive-behavioural in approach, with an emphasis on relapse prevention and the development of a “Good Life” plan, the programme helped residents to accept responsibility for their abusive past behaviour and to build on strengths to create an offence-free future. Programme content helped residents to develop victim awareness and empathy; recognise the role of deviant sexual fantasy in offending and utilise strategies for the control of such fantasies; develop self-management, assertiveness, relationships and problem-solving skills; understand links between their own childhood trauma and their offending; create relapse prevention and self-management strategies; and learn to meet their basic human needs in positive, non-abusive ways. Such programmes aim to help past offenders not to repeat their abusive behaviour – known in public health terms as ‘tertiary prevention’.

The future risk of some Wolvercote Clinic “graduates” was elevated due to an absence of prosocial adults in their lives. In response, we developed Circles of Support and Accountability, a model that recruits, trains and supervises volunteers to support known sex offenders in their local community is showing remarkable success in reducing reconviction rates in Core Members (see Article: Circles of Support and Accountability, A Safe Place to Change)

Some clinic residents also described their past struggles to manage deviant sexual thoughts and fantasies. With nowhere to turn for help in managing such thoughts, perhaps at a low point in their life or through use of alcohol, their resolve not to harm a child weakened. Adult family members and friends visiting the clinic had mostly not recognised their loved one’s sex offending at the time but, in hindsight, could see indicators or patterns of behaviour that ought to have caused them concern. There were also tell-tale signs in the behaviour – and sometimes the words – of the child victims that these ‘external inhibitors’ had not recognised, therefore leaving the child unprotected.[i]

From insights like these, in 2002 the LFF set up the Stop it Now! UK & Ireland campaign and its associated helpline. Printed materials inform adults about the risk of child sexual abuse and the signs to look out for in children or those around them. The helpline targets three principal groups:

- adult abusers and potential abusers – to help them recognise their thoughts or behaviour as harmful or abusive and seek help to change

- friends and family of adult abusers and potential abusers – to help them recognise the signs of abusive behaviour in those close to them and to seek help about actions to take

- parents and carers of young people with worrying sexual behaviour – to help them to recognise the signs of concerning sexual behaviour and to seek help about actions to take.

The risks posed by the Internet had already prompted another service development. Internet safety seminars were developed for parents of primary and secondary school children, to alert them to online dangers and protective steps they could take. And whilst adults must take primary responsibility for keeping children safe, children themselves have an important role to play in protecting themselves and each other. Seminars were therefore developed to help protect pupils from age-inappropriate sexual and violent content, online grooming and ‘sexting.’

Reflecting back to David Finkelhor’s “Four Pre-conditions model, we can see that sex offender treatment and Circles of Support and Accountability serve to increase and strengthen offenders’ internal inhibitors; but Circles also create an additional group of people who can act as effective external inhibitors to further offending. Stop it Now! campaign materials educate the public, serving to increase external inhibitors generally; and the Stop it Now! helpline strengthens the internal inhibitors of potential offenders, just as it helps other callers to be more effective external inhibitors of potential offending by those they know or love. Internet safety seminars in schools help parents become more effective external inhibitors of any offender targeting their children online; and those delivered to pupils help increase victim resistance and resilience.

Comprehensive framework for prevention

In their seminal work combining relevant theoretical perspectives, Smallbone, Marshall and Wortley (2008) have articulated and illustrated a comprehensive framework for the prevention of child sexual abuse. Their public health model distinguishes between primary (or universal), secondary (or selected), and tertiary (or indicated) prevention. Their crucial insight is that interventions may be directed to preventing sexual violence before it would otherwise first occur (primary or secondary prevention) as well as after its occurrence, to prevent further offending (tertiary prevention). Their framework situates individual offenders and victims within their natural ecological context, where risk and protective factors also operate. The resulting framework invites us to consider targets for interventions that:

- prevent offending or reoffending by offenders or potential offenders

- prevent victimisation or re-victimisation of children

- prevent an offence or further offence within a specific family or community and

- prevent an incident or recurrence of child sexual abuse in a specific situation or place.

| Targets | Primary prevention | Secondary prevention | Tertiary prevention |

| Offenders |

|

|

|

| Victims |

|

|

|

| Situations |

|

|

|

| Ecological systems |

|

|

Interventions with ‘problem’ families, peers, schools, service agencies and communities |

The practice of prevention

Whilst LFF’s origins were in tertiary interventions with offenders, victims and families, recent years have seen major expansion into primary, secondary and situation-specific prevention activities. These include:

- Parents Protect – a 90-minute child sexual prevention seminar, supported by a website and online learning programme aiming to give parents and carers information to keep their children safe.

- Hedgehogs – a five-session programme of activities and education for 10 year olds that builds self-esteem, provides age-appropriate sex education, engages with children about good and bad touch and develops strategies for responding should a sexually-concerning situation arise.

- Inform+ – a psycho-educational group-work programme for online child pornography offenders. It helps participants accept responsibility for their online offending and the harm caused to victims, consider the effects of this behaviour on personal and family relationships, and make plans for a future ‘good life’. (see also http://get-help.stopitnow.org.uk/)

- Inform is a psycho-educational programme for partners of child pornography offenders that provides support, information and advice.

- Securus Offender Management is a software programme that installs a ‘back door’ on the home computers of past sex offenders to allow monitoring of “violations” of key words and images indicative of further risky or offending behaviour.

Discussion and implications

In her recent report, the Children’s Commissioner for England (2015) recommends that ‘a strategy for the prevention of child sexual abuse, in all its forms, is developed and implemented by relevant government Departments’. This Comprehensive Prevention Framework is beginning to inform strategies for prevention at local and national levels. Over 180 different “interventions” to prevent child sexual abuse have been brought together in a free, online toolkit – ECSA – demonstrating not only how different countries are tackling the challenge of child sexual abuse, but also how these different “programmes” can be best integrated into a strategy that meets the particular needs and problems of a specific place.

Child sexual abuse is preventable, not inevitable. We need to have a plan!

References

Children’s Commissioner (2015). Protecting children from harm: a critical assessment of child sexual abuse in the family network in England and priorities for action.

Finkelhor, D. (1984). Child sexual abuse: new theory and research. New york, Ny: Free Press

Smallbone, S., Marshall, W. L., & Wortley, R. (2008). Preventing child sexual abuse: evidence, policy and practice. Cullompton, UK: Willan Publishing.

Smallbone, S., & McKillop, N. (2014). evidence-informed approaches to preventing sexual violence and abuse. In Donnelly, P. D., & Ward, C. L. (eds.) Oxford textbook of violence prevention: epidemiology, evidence, and policy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Smallbone, S. W., & Wortley, r. K. (2004). Onset, persistence and versatility of offending among adult males convicted of sexual offenses against children. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 16(4), 285–298.

Donald Findlater

Donald Findlater: following a career in the probation service managing work with sex offenders, Donald joined child protection charity, The Lucy Faithfull Foundation, in 1995 to manage the UK’s only residential assessment and treatment centre for men with allegations of or convictions for child sexual abuse – Wolvercote Clinic. He has since pioneered a number of developments in child sexual abuse prevention, including Circles of Support and Accountability, Parents Protect and Stop it Now! UK and Ireland.

Share

Like most websites, we use cookies. If this is okay with you, please close this message or read more about your options.